The digital wellbeing movement proves Microsoft's Windows Phone had one thing right

5 min. read

Published on

Read our disclosure page to find out how can you help MSPoweruser sustain the editorial team Read more

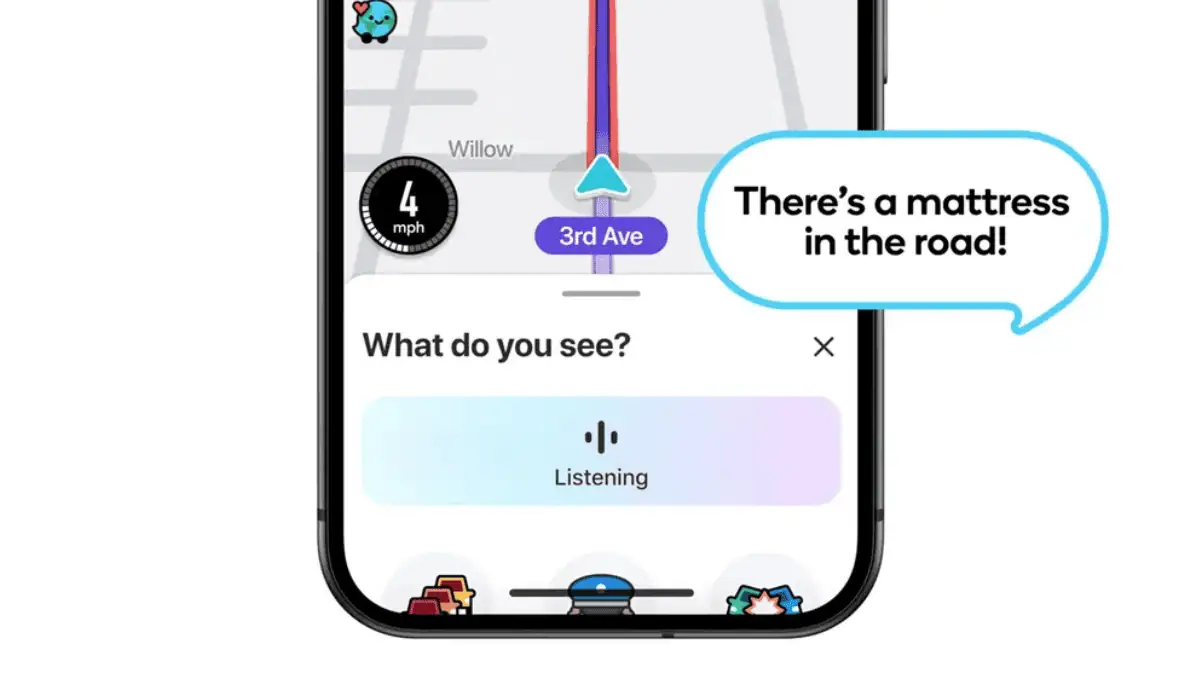

You’ve noticed it by now. It’s not just phones anymore. Every computer you have from the lowly Chromebook, the do-it-all Windows PC all the way up to the expensive MacBook ships with a notification centre to help you manage your life. As 2018 rolls to a close, every computer you have will ship with a way to tell those notifications where to stick themselves. It’s not because there’s anything wrong with notifications as a concept. We do need to know when our emails and texts come in. It’s that they’ve been abused and turned into a shackle to keep us tied to our devices indefinitely.

Microsoft’s Windows Phone is a cautionary tale at best now. The smartphone operating that like Icarus, flew too far away from the norm, towards the sun and came crashing down. The operating system had very many bright ideas, but today I’ll be thinking about one of that such ideas that only seems really good in retrospect, specifically, the live tiles. No, not the tiles themselves — but of what they embodied and the philosophy behind them. One of the major criticisms levied at Windows Phone which contributed to its failure to pick up apps was a lack of stickiness. Inherent in the concept of the live tiles was the expectation that users would get in, peep at the tiles, and get on with their lives without needing to spend too much time in each individual app. It was that philosophy that drove the content over chrome design of Windows phone. Get in, get out, get on with it.

Other platforms like iOS and Android did have that stickiness, and app developers poured in. Now, users find themselves overwhelmed by notifications and apps which want you to keep coming back. It turns out that honey isn’t the only thing that’s sticky. Mice traps are, and users are the rodents being fed little lured into this app and that.

“Cognitive neuroscientists have shown that rewarding social stimuli—laughing faces, positive recognition by our peers, messages from loved ones—activate the same dopaminergic reward pathways,” a Havard article explains, “Smartphones have provided us with a virtually unlimited supply of social stimuli, both positive and negative. Every notification, whether it’s a text message, a “like” on Instagram, or a Facebook notification, has the potential to be a positive social stimulus and dopamine influx.”

Social media and the notification center of your computer both serve to provides that stimulation. Every new Snap, text and new email is aimed at making the user feel important and lure them in. Social media users are not unaware of this effect, and view companies with suspicion. Facebook, for one, has been (inaccurately) accused of holding back notifications on Instagram to trick users into using the app more as they crave the validation.

Now people are concerned about how long they spend on social media, whether they are victims of propaganda. Whether from the Russian government or the Iranian one, prompting social media companies to respond. They worry about whether ads are too intrusive, forcing Google to ship its Chrome browser with a built-in ad blocker. Too many notifications have rendered the notification center useless, so its easier to hide or ignore them now. It’s not that these concerns are new, articles as far back as 2012 have raised these concerns. The difference now is that social media firms are watching, and listening, and paying attention to these various conversations.

When it comes to the matter of addiction, companies like Facebook, Apple and Google have enacted measures to make it easier for us to quantify how much time we spend using their services. This is not to say that they don’t want us using their services, simply that they want it to be “time well spent.”. So Instagram will now tell you when its time to get off. You’ve seen every picture since last time, go off and do something else. Apple and Google will monitor your usage and provide you with quantified data. They’ll be telling you what you do on social media, and how long you spend on each individual app, and why and wherefore. You can tell yourself to stop at any time, or even enact limits like a parent talking down to their child. “30 minutes of Instagram on Weekdays. I promise.”

Now, at the end of 2018, our smartphones and laptops all ship with a leash of sorts. Google comes with Digital Wellbeing. Apple as well. Microsoft doesn’t have the same, but Focus Assist is a technology that approximates much of the functionality. It’s not yet perfect. We’ve still been trained into checking our phones. Some device manufacturers still send errant, unwanted notifications. But it’s a start.

The valuable conversations started around regaining control of tech have been insightful. Previously, we as a society had engaged in a form of techno chauvinism. Instead of thinking about the effects of new technology, at some point we happily transitioned into playthings for big tech companies, being fed news with data from algorithms controlling things we couldn’t with information we didn’t have access to. In 2018, we took back some control of our digital lives. If only a little.

User forum

0 messages