Google explains increased in-the-wild exploits

3 min. read

Published on

Read our disclosure page to find out how can you help MSPoweruser sustain the editorial team Read more

There appears to be an increase of the phrase ‘exploit for CVE-1234-567 exists in the wild’ in the recent Chrome blogs. It is understandably alarming for most Chrome users. However, while the increase in exploits could be indeed worrying, Chrome Security explained that the trend could also be indicative of the increased visibility into exploitation. So, which is it?

The trend is likely caused by both reasons, according to Adrian Taylor of Chrome Security in a blog to clarify some misconceptions about this.

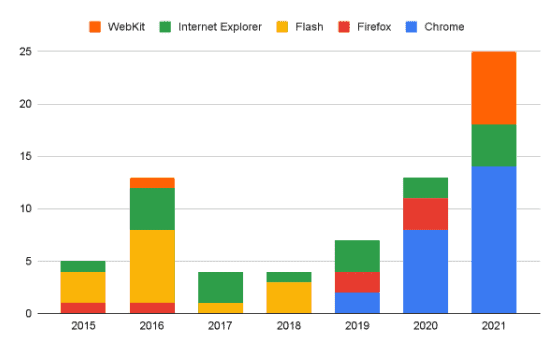

Project Zero tracked down all identified in-the-wild zero-day bugs for browsers, including WebKit, Internet Explorer, Flash, Firefox, and Chrome.

The increase in these exploitations in Chrome is quite noticeable from 2019 to 2021. On the contrary, there were no recorded zero-day bugs in Chrome from 2015 to 2018. Chrome Security clarifies that this may not mean that there was totally ‘no’ exploitation in Chromium-based browsers during these years. It recognizes having no complete view of active exploitation and the available data could have sampling bias.

So why are there a lot of exploits now? Chrome Security attributes this to four possible reasons: vendor transparency, evolved attacker focus, completion of Site Isolation project, and relation of complexity to software bugs.

First, many of the browser-makers now publish details on such exploitations through their release communications. This wasn’t the practice in the past where browser-makers did not announce that a bug was being attacked even if they were aware of this.

Second, there is an evolution in the attacker focus. In early 2020, Edge switched to the Chromium rendering engine. Naturally, attackers go for the most popular target because then, they could attack more users.

Third, the increase in bugs could be due to the recent completion of the multiyear Site Isolation project, making one bug almost insufficient to do much harm. As such, attacks in the past that only required a single bug now needed more. Before 2015, multiple web pages are only in a single renderer process, making it possible to steal users’ data from other webs with only a single bug. With the Site Isolation project, trackers need to chain two bugs or more to compromise the renderer process and leap into the Chrome browser process or operating system.

Finally, this could be due to the simple fact that software does have bugs, and a fraction of them could be exploited. The browsers reflect the operating system’s complexity, and high complexity equates to more bugs.

These things mean that the number of exploited bugs is not an exact measure of the security risk. The Chrome team, however, assures that they are working hard on detecting and fixing bugs before release. In terms of n-day attacks (exploitation on bugs that had already been fixed), there had been a marked reduction in their “patch gap” from 35 days in Chrome (76 to 18 days on average). They are also looking forward to further reduce this.

Nonetheless, Chrome recognized that regardless of the speed by which they try to fix the in-the-wild exploitation, these attacks are bad. As such, they are trying really hard to make the attack expensive and complicated for the enemy. Specific projects that Chrome is taking on include the continuous strengthening of the Site Isolation, especially for Android, V8 heap sandbox, MiraclePtr, and Scan projects, memory-safe languages in writing new Chrome parts, and post-exploitation mitigations.

Chrome is working hard to ensure security through these major security engineering projects. Users can do something straightforward to help, though. If Chrome reminds you to update, do it.

User forum

0 messages